Despite their ecological relevance, alder forests have experienced an extensive decline across all its distribution area due to different threats:

- anthropic pressures

- hydroclimatic changes

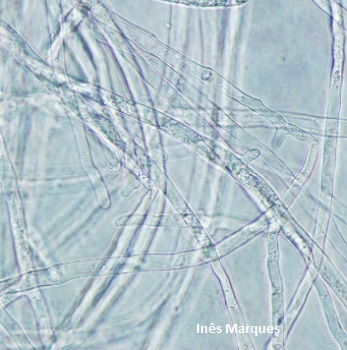

- emerging diseases

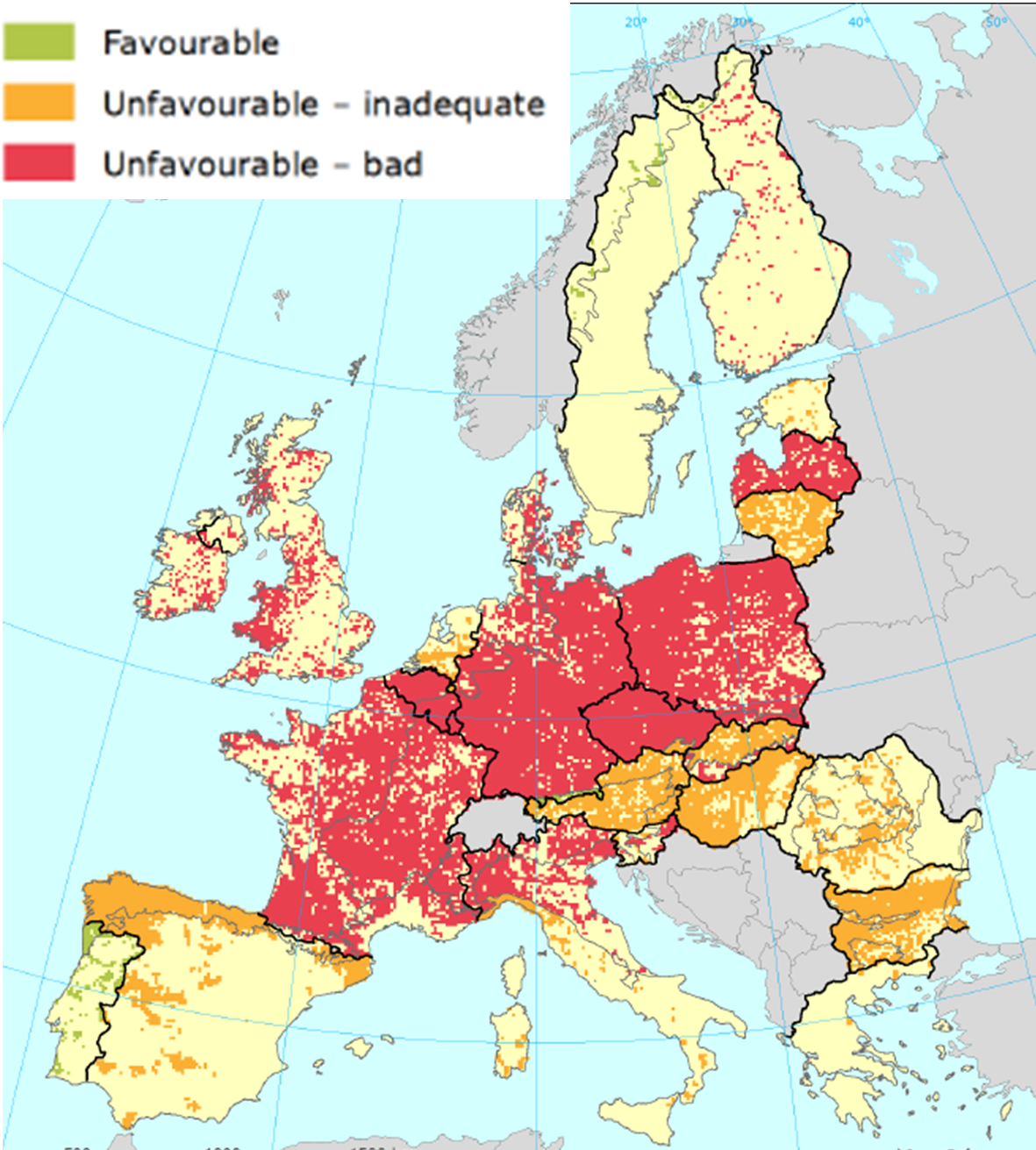

Consequently, its conservation status in most of its current range in Europe is unfavorable as seen in the figure (please note that the map was produced with data from 2007-2012, and some regions of Portugal may have changed their status to unfavorable due to emergent disease expansion; and that considerable differences are found between some countries that may be due to differences in data processing from the different states).